A 3,000-year-old gold bracelet belonging to an ancient Egyptian pharaoh has been stolen from Cairo’s Egyptian Museum, sold for less than $4,000, and melted down by a gold smelter. Egyptian authorities have arrested four suspects in connection with the theft of the artifact once owned by Pharaoh Amenemope. Museum staff discovered the bracelet missing during an inventory for artifacts scheduled for international shipment last week. The simple gold band, decorated with a single spherical lapis lazuli bead, had belonged to Amenemope, who ruled from Tanis in the Nile Delta during Egypt’s 21st Dynasty of the Third Intermediate Period. Egypt’s Interior Ministry announced the investigation results on September 18, revealing the artifact’s journey from museum to scrap metal. A museum restoration specialist initially stole the bracelet, then sold it to a silver trader. The piece passed to a jewelry workshop owner, who sold it to a gold smelter for melting. The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities launched an immediate response after the theft, circulating photographs among law enforcement and archaeological authorities. Officials established a special committee to conduct a complete inventory of the conservation laboratory where the bracelet had been stored. Forensic archaeologist Christos Tsirogiannis had warned CNN that stolen artifacts typically follow three paths: smuggling to auction houses with forged documentation, sale to private collectors, or melting for raw materials. While melting yields less profit, it makes crimes nearly impossible to trace. Despite its modest appearance, the bracelet held significant cultural and scientific value. Egyptologist Jean Guillaume Olette-Pelletier explained that ancient Egyptians considered gold the “flesh of the gods” while viewing lapis lazuli as representing divine hair. The combination made even simple pieces spiritually meaningful. “The stolen bracelet was not the most beautiful, but scientifically, it’s one of the most interesting,” Olette-Pelletier told AFP, emphasizing the research value lost when the artifact was destroyed. The case highlights ongoing challenges facing Egyptian cultural institutions as they balance public access, international exhibitions, and security for irreplaceable artifacts. The theft occurred in a restoration lab, typically considered among the most secure areas within museum facilities. All four suspects remain in custody as authorities continue investigating the theft and destruction of the 3,000-year-old royal artifact. Featured image: The bracelet was taken by a staffer at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Spanish Researchers Create First Complete 3D Map of Historic La Pileta Cave Using Advanced LiDAR

University of Seville researchers have successfully captured the first comprehensive three-dimensional digital model of La Pileta Cave in Benaoján, Málaga, using cutting-edge LiDAR technology. This breakthrough provides unprecedented documentation of one of Europe’s most significant cave art sites. Designated as a National Monument since 1924, La Pileta Cave contains several thousand graphic motifs spanning from Upper Paleolithic times through the Bronze Age. Animal figures, symbolic representations, and human silhouettes remain preserved across more than 100,000 years of archaeological sequence. Exceptional artifacts fill the cave, including a Gravettian-period lamp bearing pigment traces—recognized as one of the oldest lighting devices discovered on the Iberian Peninsula. Such discoveries make La Pileta a critical reference point for understanding European prehistoric art and culture. Researchers employed a dual-technology approach combining mobile smartphone LiDAR with terrestrial laser scanning equipment. Mobile systems provided versatility for accessing narrow passages and difficult-to-reach areas while capturing high-quality surface textures. Meanwhile, terrestrial laser scanners delivered precise, long-range measurements with exceptional reliability. Complementarity between both systems allowed scientists to obtain a complete and validated 3D model with minimal margin of error against topographic reference points, according to their study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Smartphone-based LiDAR technology uses pulsed laser beams to measure distances from emitters to cave surfaces and rock formations. This mobile approach enabled researchers to navigate complex interior spaces that traditional scanning equipment cannot reach effectively. Beyond documentation, the comprehensive digital model opens new possibilities for archaeological research, heritage management, and preventive conservation efforts. Scientists can now analyze rock art patterns without physical contact, reducing potential damage to irreplaceable prehistoric masterpieces. Virtual visitors can now explore immersive educational experiences, examining ancient artwork in unprecedented detail through this digital preservation method. A permanent record protects against natural deterioration or accidental damage. Five researchers collaborated on the project: Daniel Antón from the Department of Graphic Expression and Building Engineering, Juan Mayoral from the PAMSUR research group focusing on Middle and Upper Paleolithic studies in southern Iberia, María Dolores Simón and Miguel Cortés from the Department of Prehistory and Archaeology, plus Rubén Parrilla from PAMSUR and Portugal’s University of Algarve ICArEHB research center. Featured image: Digital model of La Pileta cave. Credit: D. Antón et al., Journal of Archaeological Science (2025)

Revolutionary Laser Method Reveals Age of Chinese Dinosaur Eggs for First Time

Fossil hunters struck gold in China’s Hubei Province, where ancient dinosaur eggs have finally revealed their true age through groundbreaking scientific techniques. For the first time in paleontological history, researchers have successfully dated dinosaur eggs directly, pinpointing their age at 85.9 million years old. The Qinglongshan site holds special significance as China’s first national dinosaur egg fossil reserve, housing more than 3,000 fossilized eggs spread across three locations. Dr. Bi Zhao and his team from the Hubei Institute of Geosciences employed what they call an “atomic clock” technique to crack the age mystery that has puzzled scientists for decades. Among the clutch of 28 eggs embedded in siltstone, researchers identified most specimens as belonging to Placoolithus tumiaolingensis, part of the Dendroolithidae family. These particular eggs, characterized by their highly porous structure, have been discovered in both China and Mongolia, suggesting widespread distribution during the Late Cretaceous period. The breakthrough came through in-situ carbonate uranium-lead dating, a precision method that targets tiny fragments of eggshell material. Scientists fire micro-lasers directly at carbonate minerals within the shell, vaporizing them into aerosol particles. Mass spectrometers then analyze these particles, counting uranium and lead atoms with extraordinary accuracy. “We fired a micro-laser at eggshell samples, vaporizing carbonate minerals into aerosol,” Zhao explained in their published research. Since uranium naturally decays into lead at a consistent rate over millions of years, researchers can calculate precise ages by measuring accumulated lead content. Results showed remarkable consistency, with measurements falling within a 1.7 million year margin of error. This level of precision represents a significant advancement over traditional dating methods, which often relied on surrounding rock layers rather than the fossils themselves. Beyond solving an age-old mystery, these findings open new windows into Late Cretaceous climate patterns. The dated eggs suggest dinosaur adaptation to cooling temperatures that characterized this geological period, providing crucial data points for understanding environmental changes that ultimately led to dinosaur extinction. Recent paleontological discoveries in China have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur reproduction and behavior. Similar dating techniques applied to Jurassic sauropod bone cavities from Sichuan Basin have yielded ages of 165.3 million years, demonstrating the broader applications of advanced dating methods across different geological periods. The timing of these eggs places them squarely within the Late Cretaceous cooling phase, when Earth’s climate shifted dramatically enough to threaten dinosaur survival. Scientists believe these fossil records will prove invaluable for reconstructing ancient environmental conditions and understanding how prehistoric creatures responded to climate stress. “Our achievement holds significant implications for research on dinosaur evolution and extinction, as well as environmental changes on Earth during the Late Cretaceous,” Zhao noted. The research team’s work transforms static fossils into dynamic storytellers, narrating Earth’s ancient history with unprecedented detail and accuracy. This technological breakthrough promises to reshape paleontological research methods worldwide. As the first successful application of carbonate uranium-lead dating to dinosaur eggs, it establishes a new standard for direct fossil dating that could revolutionize how scientists approach prehistoric timelines and evolutionary studies. Featured image: Numerous dinosaur eggs have been found in Shiyan, China, but their age has been unknown until now. Credit: Dr. Bi Zhao

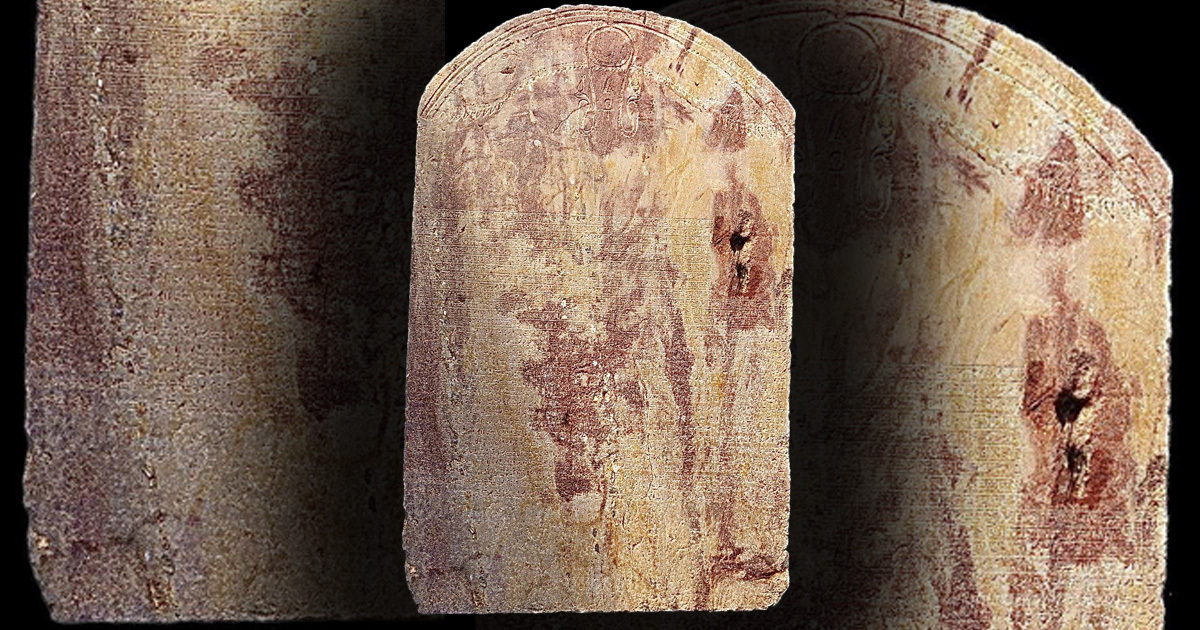

Egyptian Archaeologists Uncover Historic Hieroglyphic Stone Second Only to Rosetta Stone

Egyptian excavators working in Sharqia Governorate have pulled a massive sandstone tablet from the earth that scholars are calling the most important linguistic discovery in more than a century. The stone bears a complete hieroglyphic version of the Canopus Decree, issued by Pharaoh Ptolemy III in 238 BC. Standing over four feet tall and weighing several tons, this particular copy differs dramatically from previous finds. While other versions of the Canopus Decree contain text in three languages (hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Greek), this specimen contains only hieroglyphic script. That makes it exceptionally valuable for linguists trying to decode the picture-based writing system of ancient Egypt. The archaeological team from Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities made the discovery at Tell el-Pharaeen, an excavation site in Husseiniya. The find represents the first complete version discovered in over 150 years, according to ministry officials. When French soldiers accidentally uncovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799, they launched a revolution in understanding ancient Egyptian civilization. But the Rosetta Stone wasn’t working alone. The Canopus Decree has long been considered its most important companion text. Six copies of the Canopus Decree have been found over the years, two complete and three fragments. The first two complete versions were unearthed in 1866 at the ancient city of Tanis. Until now, those remained the only intact examples. Unlike the Rosetta Stone, which helped decode Egyptian writing through parallel translations, this new discovery offers something different. The entirely hieroglyphic text provides researchers with a pure example of the script without needing to cross-reference other languages. The decree itself tells a story of royal sorrow and administrative efficiency. Ptolemy III’s infant daughter Berenice died in February 238 BC when she was barely a year old. The grieving pharaoh ordered priests throughout Egypt to honor her memory and establish new religious practices. The tablet’s surface displays intricate craftsmanship. A winged solar disk crowned with two royal cobras dominates the top section, while thirty lines of hieroglyphic text fill the stone below. The decree describes Ptolemy III and his wife Berenice II as “beneficent gods” and lists their accomplishments. According to the hieroglyphic text, the royal couple donated generously to Egyptian temples, maintained peace within the kingdom, and reduced taxes during poor Nile flood years. Most significantly for modern calendars, the decree established the leap-year system by adding one day every four years. Dr. Mostafa Waziri, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, emphasized the discovery’s linguistic importance in the ministry’s announcement. The find “enriches our understanding of Ptolemaic royal and religious texts, while also deepening our grasp of ancient Egyptian language”. Previous Canopus Decree copies included parallel texts in Demotic and Greek, which helped scholars understand individual hieroglyphic symbols. This monolingual version provides researchers with extended hieroglyphic passages that can be analyzed independently, potentially revealing new grammatical structures and vocabulary. The decree also contains historical details that archaeologists are still examining. It mentions religious festivals, priestly rankings, and administrative policies that shed light on how the Ptolemaic dynasty governed Egypt during its peak years. Tell el-Pharaeen sits on the ruins of ancient Imet, once a thriving urban center in the eastern Nile Delta. The Canopus Decree mentions the submerged city of Heracleion, adding another layer of historical significance to the text. Previous excavations at the site have uncovered temples, residential buildings, and artifacts dedicated to the goddess Wadjet. The location sits about 120 miles northeast of Cairo, near Egypt’s northern coastline. The discovery team continues working at Tell el-Pharaeen, hoping to uncover additional artifacts from the Ptolemaic period. Given the importance of this find, archaeologists expect increased international attention on the site. Ministry officials have not yet announced plans for displaying the newly discovered tablet, though it will likely join other significant archaeological finds in Egyptian museums. The stone’s size and condition make it suitable for public exhibition once conservation work is completed. Top image: The complete Canopus Decree Stela discovered in Sharqiya (Facebook)

Bronze Celtic Warrior Found Among 40,000 Artifacts in Bavarian Excavations

German archaeologists have uncovered a three-inch bronze Celtic warrior figurine among more than 40,000 artifacts during three years of excavations at Manching oppidum in Bavaria. Standing just under three inches tall, the miniature soldier wears chest armor and holds a shield and sword, displaying remarkable detail despite its small size. Researchers determined the figurine was made using lost-wax casting—a process involving crafting a wax model, coating it in clay, then pouring molten bronze into the hollow mold after the wax melts away. A loop at the top suggests the statuette was intended to be worn as a pendant. Founded in the late fourth century B.C., Manching was one of central Europe’s most important Iron Age urban centers, housing up to 10,000 people at its height. Over three years, excavation teams recorded 1,300 new archaeological features across the sprawling settlement. Fish scales and bones within trash deposits provided the first direct evidence that residents consumed fish along with their usual diet of grains, beef, and pork. Previous research had suggested fish consumption based on the site’s location near waterways, but physical proof had been lacking until now. Manching’s archaeological importance stems from its position as a major Celtic settlement that operated from roughly 250 B.C. to 80 B.C. Excavations continue at the site, with researchers documenting each discovery to build a comprehensive picture of Celtic urban life before Roman conquest. Header image: Bronze Celtic warrior figurine Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation

Ancient Tablet Reveals Lost Sumerian Myth: Hero Fox Saving an Anunnaki God

For 4,400 years, a small clay tablet lay hidden inside the ruins of the Ancient Sumerian city of Nippur (in what’s now southern Iraq). This tablet may be miniscule but it reveals a forgotten myth that expands Mespotamian storytelling. Today, this ancient tablet (labeled Ni 12501) rests in Turkey’s Istanbul Archaeological Museums, where University of Chicago’s Sumerologist Jana Matuszak decoded its secrets this year. Published in the journal Iraq, her work unveils a tale of a cunning fox undergoing a daring rescue mission to save the Anunnaki storm god Ishkur. The problem: the storm god’s trapped in Kur (the Mesopotamian underworld) of all places, where the fox must navigate through its perils lest the world collapses into chaos. This discovery sheds new light on the beliefs of one of humanity’s earliest civilizations, and we’ll explore below on how this story stands out from other Mesopotamian legends. Lost & Found From Nippur Dug up in the 19th century from Nippur’s ancient ruins, the Ni 12501 tablet is no larger than a smartphone, with a forgotten story to tell. Nippur once stood as the spiritual heart of Sumer and was home to Enlil; once the revered king of the Anunnaki gods. Crafted around 2540–2350 BCE, the tablet’s cuneiform script lay unread for decades with its broken fragments barely a third surviving tucked away in obscurity. Then during the 1950s, Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer gave the tablet a nod; having featured its image in his book From the Tablets of Sumer. The tablet remained a puzzle, however, that was until Jana Matuszak’s ingenious 2025 work finally unraveled its secrets. Using high-tech imaging and linguistic skill, Matuszak decoded the faint script. Her study shows Nippur’s role as a hub for sacred stories where tales of gods explained life’s highs and lows such as floods to crop failures. This tablet’s revival adds a new chapter to Sumerian lore, proving that there’s still much to learn from ancient archives. A Myth of a Trapped God and a Bold Fox The myth centers on the storm god Ishkur whose power over rains fed Mesopotamia’s fields, before being mysteriously trapped in Kur—Sumer’s grim underworld of shadows and monsters. As of 2025, it is not yet known why or how the Anunnaki got himself imprisoned in the underworld. However, Ishkur’s absence sparks chaos in the mortal realm: rivers dry up and harvests fail. Ishkur’s father Enlil then gathers a divine council in Nippur to find a rescuer that could save the trapped god and bring back the rains. None of the Anunnaki stepped up, as many of them were wary and uneasy of the underworld’s dangers. Then, unexpected help came forth in the form of a sly fox who offered to volunteer in saving the Anunnaki king’s son. The cunning fox manages to dodge the underworld’s traps by hiding ritual offerings; a trick seen in other Sumerian stories… but the tablet breaks off leaving us wondering if the fox ever freed Ishkur. It would appear that foxes held a special place in Mesopotamian tales, in which they’re recognized back then as crafty intermediary agents in the world of gods and humans. The fox’s symbolism as a trickster figure is older than previously thought, and its role survives all the way in present day in peoples’ memories through classic fables, children’s tales and even cartoons. This lone furry hero’s boldness may suggest that Sumerians cheered for clever underdogs, whilst it’s also a theme that echoes across world folklore involving trickster figures (often in the guise of similar animals) that outsmart powerful entities or environments. Pitting the Fox’s Wits Against The Underworld This myth reveals glimpses of Sumerian life where city-states like Nippur, Ur, and Uruk flourished from 4000 to 2000 BCE, shaping early writing and religion. Tales like this bound Mesopotamian communities to their land, especially when peoples’ fields and crops are reliant on rain. Unlike the divine rescues in myths like Enki and Ninhursag or Inanna’s Descent where gods or humanoid figures are at the center of the narrative, this story marks a rare animal hero with the fox’s cunning taking the spotlight. Perhaps this narrative is a local Nippur specialty, though it’s not confirmed. Jana Matuszak’s decipherment of Ni 12501 opens a door to the vast treasures of cuneiform collections, where numerous clay tablets lie untranslated in museums waiting to be revived. Advanced digital imaging now breathes life into these faded scripts, letting scholars like Matuszak piece together tales lost for millennia. One can hope that new finds in Iraq or archives might complete this tale; perhaps revealing extra scenes from this myth or unveiling new sagas of Sumer’s vibrant world. Though the story’s ending fades into mystery, the fox’s bold wits against divine chaos shows how even an ordinary animal can challenge primal cosmic forces by just using mere cleverness. This 4,400-year-old tablet may be fragile and having endured the tests of time, but it still whispers ancient wisdom that animates our modern imaginations. Much like how the fox is able to outsmart the perils of the underworld using wits, this lost Anunnaki myth may inspire our own journeys in outsmarting challenges in an ever-changing world. Top image: Arabian red foxes (Vulpes vulpes arabica) are a fox species found in Southern Iraq. Source: CC BY 4.0. Taken by Alahamali70. Statue of Hadad (another name of the Anunnaki god Ishkur) presented by Felix von Luschan et al. Source: Public Domain. References:

Medieval Health Tips Coming Back Today—Old Remedies to Social Media

Imagine yourself flipping through a worn and wrinkly 1,000-year-old book, before spotting a scribbled note in the margin about curing a headache with crushed herbs. That’s not the “Dark Ages” of superstition we’ve all heard about. This is a glimpse into a world where medieval Europeans were clever with their health and had surprisingly resourceful treatments. A new project called the Corpus of Early Medieval Latin Medicine (CEMLM) has dug up hundreds of these forgotten medical notes—nearly doubling what we knew about health practices before the year 1000. What’s more is that some of those old remedies sound like something you’d see in a social media wellness post on Instagram or TikTok today. It Seems The “Dark Ages” Weren’t Too Much Dark Let’s ditch the “Dark Ages” stereotype for a second. The Early Middle Ages in Europe (those centuries before 1000 CE) weren’t always about people hiding from progress. Folks were out there experimenting, mixing plants and even animal bits to fix ailments, figuring out what worked through practical trial and error. The CEMLM (which is backed by the British Academy and a team from New York’s Binghamton University together with Fordham, St. Andrews, Utrecht, and Oslo universities) has been combing through old manuscripts to show just how savvy medieval practitioners were. The international research team has uncovered a pile of medical texts that prove health was a big deal back then, not some mumbo jumbo. Binghamton University historian Meg Leja, who wrote Embodying the Soul: Medicine and Religion in Carolingian Europe, sums it up smooth: “People were engaging with medicine on a much broader scale than had previously been thought. They were concerned about cures, they wanted to observe the natural world and jot down bits of information wherever they could in this period known as the ‘Dark Ages.‘” No fancy labs. Just sharp observation and a knack for jotting down results. The project’s new online database lays it all out, showing that medical know-how wasn’t locked away with elite scholars—it was everywhere. Ranging from monasteries to even village homes. Hidden Health Tip Gems in Old Medieval Books Here’s the cool part: the CEMLM didn’t just focus on famous texts by guys like Hippocrates or Galen. They found medical tips tucked away in the oddest places—scribbled in the margins of books about poetry, theology or even grammar. Little notes like these reflect how much people cared about staying healthy. By digging up these overlooked bits, the international team has nearly doubled the number of known medical manuscripts from before the 11th century. It’s like stumbling across a secret stash of recipes in your ancestors’ attic. Meg Leja and the team spent two years scouring libraries across Europe: from dusty monastery shelves to university archives, puzzling out faded Latin on parchment that’s seen better days. With the British Academy’s support, they’ve put together an online catalog that’s a goldmine for anyone curious about the past. It shows a world where healing was practical, rooted in local plants and traditions, not just copied from some Ancient Greek playbook. Ye Olde Remedies That Feel Familiar Some of these old health tips are weirdly modern. One recipe says to grind up peach pits, mix them with rose oil, and rub the paste on your forehead for a headache. Sounds quirky, but a 2017 study in Complementary Therapies in Medicine found rose oil can ease migraines because it fights inflammation. Not too shabby for a medieval fix! Back then, healers leaned hard on nature—think chamomile, sage, or rose, mixed with oddball ingredients like animal scraps. The Anglo-Saxon Bald’s Leechbook from the 10th century is full of these recipes, blending herbs and animal bits. A 2015 University of Nottingham study even tested one of its eye infection cures and found it could knock out antibiotic-resistant bacteria. That’s a 9th-century remedy giving modern pharmaceuticals a run for its money. Then here’s the fun part: today’s wellness crowd is all over this stuff. Scroll through Instagram, Facebook or TikTok, and you’ll see social media influencers hyping herbal salves or detox cleanses that sound like they could’ve come straight from a medieval monk’s notebook. The CEMLM’s findings show that medieval health hacks weren’t just practical—they hit a chord that still resonates, like our obsession with “natural” remedies today. More Than Just Old Recipes The CEMLM’s work is rewriting how we see the Early Middle Ages. Forget the idea that these folks were anti-science—they were out there observing, experimenting and writing it all down. Take the 9th-century medical text Lorsch Pharmacopoeia from the Carolingian era—it’s packed with practical tips that blend local know-how with bits of classical info. The project’s catalog also shows how health was everyone’s business. Monks, scribes and even regular folks were jotting down cures in whatever books they had handy. It’s not unlike today’s social media, where anyone can share a health tip. By making these texts available online, the CEMLM lets us see how the quest for wellness is something humans have always chased. What’s Next for Old Remedies Set In Today’s Times? The CEMLM team isn’t done yet. They’re working on new editions and translations to make these texts easier for students and researchers to dive into. Unlike older collections that focused on big-name authors, this project shines a light on the everyday wisdom of medieval European communities. They’re also planning to add more manuscripts to the catalog, which could show how medical tricks varied from, say, Anglo-Saxon England to Carolingian France. There’s even room for some cool crossover work. By linking these old remedies to modern science—like that rose oil study—researchers could test more cures to see what else holds up. The University of Nottingham’s work with medieval recipes is already showing how history and science can team up in surprising ways. The Corpus of Early Medieval Latin Medicine has pulled back the curtain on a time when people were anything but “dark.” They were clever, curious, and dead-set on healing. Able to utilize nature’s gifts to whip up remedies that

Glossopetrae: From Tongue Stones to Shark Teeth

Imagine yourself stumbling upon a jagged triangular stone glinting in the Mediterranean sun, with its sharp edges hinting at a mysterious past. What you’ve just stumbled upon was once known as glossopetrae or “tongue stones”. For centuries, people across Europe believed these objects were the petrified tongues of mythical serpents or dragons. Glossopetrae had been worn as amulets; ground into medicinal powders; even revered as talismans as these curious objects carried tales of magical or divine power. However, the truth behind glossopetrae is even more remarkable: today we recognize glossopetrae as ancient fossil shark teeth that have been buried in the Earth for millions of years. A Mythical Beginning In the Ancient Mediterranean, ranging from the rocky shores of Malta to the bustling markets of Rome, glossopetrae were objects of wonder. Their name is derived from the Greek words glossa (tongue) and petra (stone), reflecting their striking shape—pointed, serrated and eerily tongue-like. To the people of classical antiquity, these were treated as no mere rocks. In Malta, locals believed these peculiar fossilized stones were linked to Saint Paul’s legendary shipwreck on the island around 60 CE. According to the tale, Saint Paul survived a venomous snake bite, rendering all snakes harmless. This event tied to faith has led locals to associate the fossilized tongue stones found in Malta’s cliffs with his miraculous act. Though no archaeological evidence supports this legend directly, it remains a blend of cultural storytelling and natural curiosity that shaped their views on glossopetrae. Elsewhere, the Ancient Roman naturalist Gaius Plinius Secundus (otherwise known to many as Pliny the Elder) spun a different tale in his Naturalis Historia (77–79 CE). Pliny the Elder speculated that glossopetrae were gifts from the heavens, falling during lunar eclipses and somehow resembling crescent moons. This enchanting idea highlighted the ancient tendency to attribute cosmic origins to mysterious objects. Across cultures, glossopetrae were prized as charms to ward off misfortune, cure snakebites and neutralize poisons. Nobles wore them as pendants, and apothecaries ground them into powders for antidotes, having been convinced their serpentine origins held potent magic. The Truth Beneath the Myth For all their allure, glossopetrae were not actual tongues, nor did they rain from the stars. As revealed earlier, these objects were the fossilized shark teeth formed millions of years ago, primarily from the Cenozoic era (66 million years ago to present). However, fossilized shark remains can extend across other geological periods, reflecting sharks’ extensive evolutionary history. Sharks, including Megalodon, shed thousands of teeth over their lifetimes, many of which sank into ocean sediments and fossilized into calcium phosphate. These shark teeth—ranging from small daggers to hand-sized giants—washed ashore or were unearthed in places like Malta, Italy and North Africa, where they puzzled ancient peoples’ minds. The connection to sharks remained obscure for centuries, as most people in antiquity and the Middle Ages struggled to conceptualize these stones as remnants of living creatures. While some philosophical traditions speculated that fossils grew spontaneously or were shaped by natural earthly forces, others proposed more naturalistic theories, such as petrification through fluids. It wasn’t until the Renaissance that scholars like Konrad Gesner and Nicolaus Steno replaced myth with evidence, laying the scientific groundwork for paleontology. The Renaissance Revolution In the 16th and 17th centuries, a wave of curiosity swept through Europe, and glossopetrae became a focal point for scholars eager to decode nature’s secrets. One of the first to challenge old beliefs was Swiss naturalist Konrad von Gesner who noted the striking similarity between glossopetrae and modern shark teeth in the 1550’s. His observations planted seeds of doubt about their mythical origins. The decisive breakthrough came in 1616, when Italian scholar Fabio Colonna published Dissertatio de Glossopetris. Comparing fossil teeth to those of living sharks, Colonna argued convincingly that glossopetrae were not serpent tongues but rather ancient shark remains. His work established the base for a scientific revolution. The most focal moment then occurred in 1666-1667, when renowned Danish anatomist Nicolaus Steno received a massive great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) head from the Grand Duke of Tuscany. As Steno dissected it in Florence, he detected an astonishing find: the shark’s teeth were identical in shape to the glossopetrae he’d studied. In his groundbreaking work during, Canis Carchariae Dissectum Caput, Steno declared that these “tongue stones” were thus fossilized shark teeth. His findings demystified glossopetrae from their mythical origins, and instead proved that the fossil teeth were remnants of long-extinct life that once swam the prehistoric oceans. Steno’s work, alongside contributions from others like Fabio Colonna, helped birth paleontology. While figures like Leonardo da Vinci had speculated about fossils’ marine origins and Robert Hooke had explored their organic nature, it was Steno’s meticulous evidence that turned the tide. From this point, human understanding evolved from fantastical speculation into scientific fact. A Legacy of Wonder The story of glossopetrae is more than a tale of mistaken identity—it’s a testament to humanity’s quest for truth. From Maltese cliffs to Renaissance dissecting tables, these fossilized shark teeth have captivated imaginations for millennia. Once revered as divine relics or cosmic gifts, they now stand as evidence of ancient oceans teeming with predators like the Megalodon, whose massive teeth likely numbered among the glossopetrae treasured by our ancestors. Today as we celebrate Shark Week, glossopetrae remind us how curiosity and evidence can transform myth into knowledge. They invite us to marvel at the creatures that ruled the seas millions of years ago and to celebrate the thinkers who dared to question ancient tales. So, the next time you hold a fossilized shark tooth in your hand, imagine the journey it’s traveled—from an ancient ocean to a medieval amulet, and finally to a symbol of scientific discovery. Header Image: Fossil shark teeth of various shapes and sizes. By Luca Oddone. Source: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Ancient Roman Victory Relief Found at Vindolanda Fort

On the windswept hills close to Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, at the Vindolanda fort, archaeologists have found a stone relief of Victoria, the goddess of victory. This sarcophagus, completed around AD 213 and measuring 47 cm tall, 28 cm wide and 17 cm deep, likely marked the royal entrance of a grand archway celebrating Rome’s success over Britain’s new northern border reached at the end of the Severan wars. As a result of decades of hard work by volunteers, we can now glimpse the lives of soldiers, skilled artisans and the everyday culture of a Roman outpost. What can we learn about a goddess from her journeys at the empire’s borders? Long-serving volunteers Jim and Dilys Quinlan found the relief while they were digging in a layer of rubble over an infantry barracks, for the Vindolanda Trust. We can see from its details that an artist, commissioned to capture a major battle, was responsible for sculpting this statue. Dr. The exceptional rarity of such discoveries in Roman Britain, shown by Director Andrew Birley, reflects the importance of the Roman relief in Devon. Professor Rob Collins found that the carving is connected to an extreme monumental archway from the post-Severan era, when Emperor Septimius Severus succeeded in defeating tribes in the north. Curator Barbara Birley says that since the stone mixes a wide range of color, experts are searching for evidence of old pigments commonly added to Roman statues to livens their textures. As the Roman match for Nike, Victoria was much more than a goddess, standing for divine approval and the fighting skills of soldiers at the busy fortress of Vindolanda. Such relief probably reflected that the fort had recovered, offering military strength and cultural activities after the Severan wars. It is clear from the barracks that the statue influenced daily activities of soldiers far from central Rome. Apart from its artistic value, the stone reflects what happened in ancient Ireland: how a sculptor worked, men hoped for victory and these two societies waited through the ages to be united. Vindolanda, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is important to the communities of Northumberland because its stones form part of the area’s heritage. It shows Italy’s pride and inspires us to think about how local tribes stood up against the ruling power. It will be presented at Vindolanda’s exhibition called “Recent Finds” in 2026, bringing visitors from around the world to reflect on the history of conquest and endurance. Learn more at: https://www.vindolanda.com/

Dacian Treasure Horde found in Romania May Hint at Lost Enclave

Two amateur metal detectorists have found something unexpected in the commune of Breaza in Mureș County, in the heart of Romania. A Dacian treasure trove of silver artifacts has been found, dating back some two thousand years. The Dacians were skilled metalworkers and this new discovery does not disappoint. The horde, found by detectorists Dionisie-Aurel Moldovan and Sebastian-Adrian Zăhan and reported by the Breaza Mures Municipality, consists of six richly decorated pieces. Three brooches, a bracelet, a neck chain and a belt of interlocking plates are all crafted in the distinctive Dacian style. What is surprising about these finds however is where they were found. There are no records of Dacian presence in this part of Romania, at any point in history. These finds, according to our current understanding of the Dacians, simply should not be here. Nor were these the trinkets of some passing Dacian merchant. The craftsmanship of the items argues for them belonging to someone very high up in Dacian society. The flared ends of the bracelet in particular, with their intricate and delicately worked leaf designs, look like something only a member of the Dacian ruling class could afford. Why, then, are they here, far from any known Dacian settlement? There are two main theories, neither entirely satisfactory but both a possibility given these unexpected finds. The first possibility is that these were a secret cache of valuables, hidden away to be retrieved by a retreating Dacian in a time of crisis. Were they hidden out here to buy some lost Dacian lord his way to freedom, only to never be recovered? Or, perhaps even more interestingly, is it our knowledge of the Dacians themselves which is lacking. Are these treasures hidden here because the Dacians did in fact inhabit this region of central Romania, lost to time and unknown for millennia? If the latter is true, it would suggest that there is much more to be found in the region than was previously thought. Perhaps there is a Dacian settlement in the area, waiting just beneath the surface for some enterprising detectorists to stumble upon it. Header Image: The silver artifacts recovered were far from any known Dacian presence. So, what were they doing here? Source: Breaza Mures Municipality.

“I’ll Drink to That!” Everyone Loved Wine in Bronze Age Troy, New Study Finds

Homer’s Iliad is a problematic text. On the one hand, it tells us of a time before the Bronze Age Collapse in the twelfth century BC, a lost era before the Greek palaces burned and the survivors of catastrophe forget, for centuries, how to read or write. Such resources detailing this world are few, and Homer’s is without a doubt the finest record of this ancient time. On the other hand, it is clearly a work of fiction, at least in part. Gods and monsters roam the world of Homer’s Mediterranean, heroes murder soldiers by the dozen. We don’t even know if the Trojan War ever happened, and picking the accurate detail from the rhetorical flourishes can sometimes be a challenge. However there is much to be learned from these epic tales, and one such detail concerns the depas amphikypellon. This cylindrical goblet with two curved handles is mentioned in the Iliad and examples were found by the 19th century archaeologist (and vandal) Heinrich Schliemann during his excavations of what he believed to be Troy. It is a neat link between the archaeology and Homer’s tale. Such vessels were often thought to be used for drinking wine, a practice believed to be common among the elite of Mycenaean Greek society. And this was indeed recently confirmed in a study published in the American Journal of Archaeology: acids derived from fruit have been found inside such goblets: they were indeed wine cups. But here’s where it gets interesting. Similar analyses conducted on a wide range of cups and beakers from the ruins of Schliemann’s Troy have also been shown to contain the same fruit acids. Not withstanding the meanest and lowest rough-hewn drinking cup, all seemed to be used for drinking wine. Not only were many of these more primitive drinking vessels found to contain wine residue, their location further reinforces the idea that these cups were not used by the elite. They were found in areas associated with the common population of the great city, outside the central citadel of Troy. This challenges the idea that wine drinking was enjoyed only amongst the elite, or for ritual reasons only. It seems instead that everyone in Bronze Age Troy enjoyed drinking it; what a party that must have been. More work needs to be done to confirm the full extent of wine drinking amongst the population of Troy. But at the moment it seems that we will need to totally re-evaluate our understanding of wine production, distribution and consumption in the Bronze Age. If it isn’t just the elite, there must have been an awful lot more of it around, for a start. Wine cultivation is not an easy process, which is partly why we thought only the elite would have access to it. As it happens, Troy is in a region well suited to wine production which may mean it is only a local phenomenon, a surplus to be enjoyed by the entire population. However it is clear what needs to happen next: we need to start looking inside the cups and beakers of other Bronze Age cultures. Was everyone drinking wine? Header Image: Examples of the depas amphikypellon found near Schielmann’s Troy. Source: Internet Archive Book Images / Public Domain.

Curiouser and Curiouser: Iron Age Hoard found in Britain was Deliberately Burned

The island of Great Britain has a strange and unusual history, and part of the challenge is connecting the history we know with the landscape we see today. As more and more discoveries are made, the story only gets weirder. We have stories of battles, kings of ancient myth. We know of invading armies and hear from continental accounts of a mysterious land of forests and mists, warlords and druids, great stone circles and enormous earthworks. And we see this evidence in the landscape even to this day. But the problem comes in putting all the pieces together. It is always hoped that new discoveries will shed light on an ancient past, but this is not always the case. A new find, a hoard near the Yorkshire village of Melsonby, is a perfect example of this proliferating confusion. The hoard, discovered by detectorist Peter Heads and excavated over three years by a team from Durham University, is one of the most significant such finds ever made. More than 800 artifacts have been uncovered, dating back around 2,000 years. Iron-shod wheels have been found, probably from a wagon or possibly even a chariot. Great cauldrons and bowls were probably used for mixing wine. Elaborate bridle bits and pieces of horse harnesses decorated with Mediterranean coral and colored glass have been pulled from the earth. But what is strange about this discovery is that all the items appear to have been burned. This was not some funeral pyre, no human remains were found. So why did these ancient people destroy their most precious possessions? For now we can only speculate. Professor Tom Moore, a British and European Iron Age specialist from Durham University’s Department of Archaeology theorizes that they may have been torched in a conspicuous display of wealth. “Whoever originally owned the material in this hoard was probably a part of a network of elites across Britain, into Europe and even the Roman world. The destruction of so many high-status objects, evident in this hoard, is also of a scale rarely seen in Iron Age Britain and demonstrates that the elites of northern Britain were just as powerful as their southern counterparts.” But this just raises more questions. Who was there to witness this ceremonial destruction, who were the elites trying to impress? What strange ceremony took place here out in the wilds of northern Britain which left so much of value burned or broken? For now there is still much to be done, but if we can piece this hoard back together there is much it can teach us about a lost era of British history. In understanding what happened here, we can perhaps bring the ancient peoples of this dark, misty island into the clear light of day. Header Image: In understanding why this Iron Age hoard was deliberately destroyed, it is hoped that we will gain an insight into the strange world of Iron Age Britain. Source: Durham University.