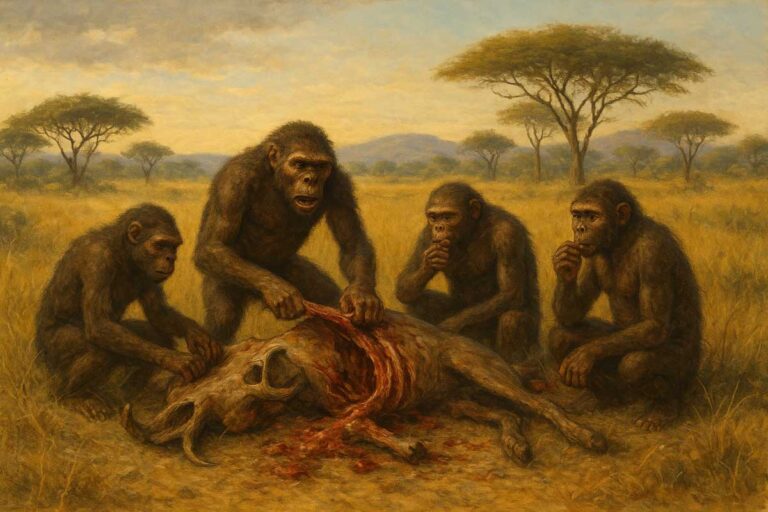

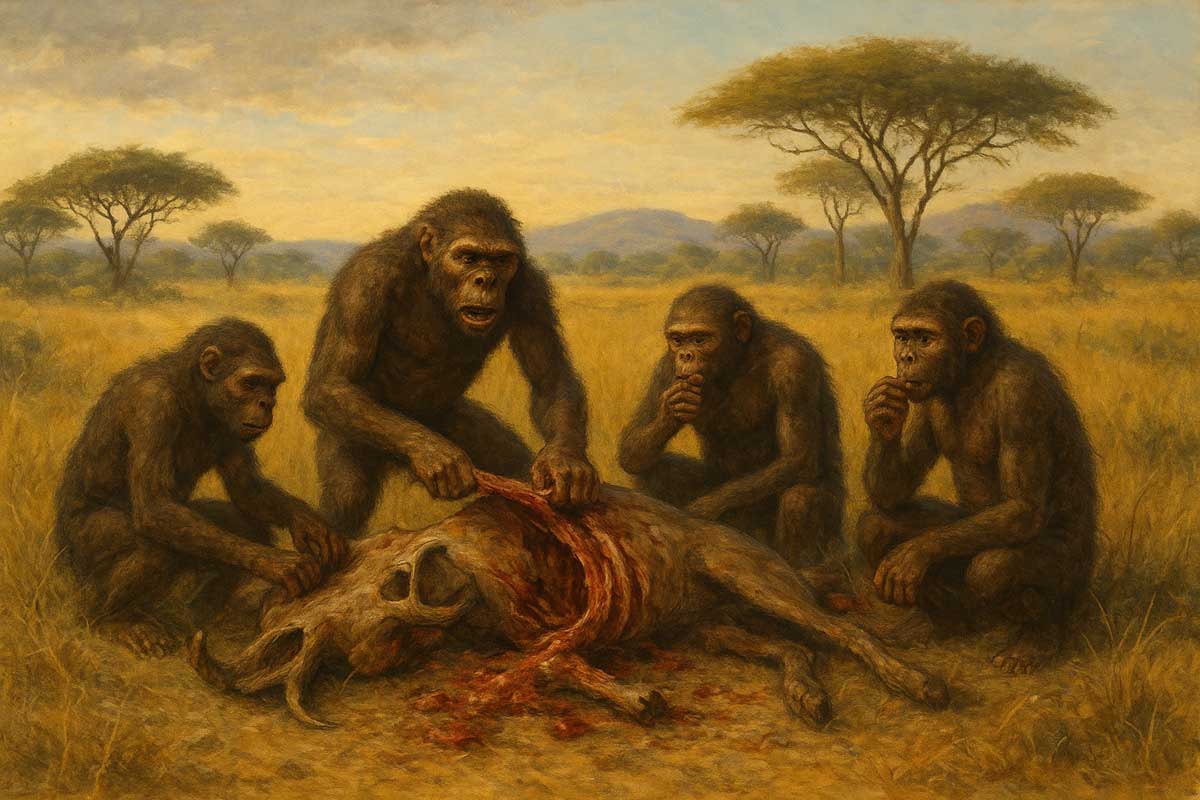

A new study challenges long-held assumptions about human evolution by repositioning carrion consumption as a fundamental survival strategy rather than a primitive behavior our ancestors abandoned. The research, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, presents scavenging as a consistent and highly efficient practice that shaped our species from the earliest hominins to modern populations.

Ana Mateos and Jesús Rodríguez from Spain’s National Research Center on Human Evolution (CENIEH) led the multidisciplinary team, which included researchers from IPHES-CERCA, IREC-CSIC, IPE-CSIC, Universidad Miguel Hernández, and several Spanish universities. Dr. Jordi Rosell from Universitat Rovira i Virgili and Dr. Maite Arilla, both IPHES-CERCA researchers, contributed to the paleontological and archaeological synthesis.

The study dismantles three major misconceptions about scavenging. For decades, scientists portrayed carrion as scarce and unpredictable, inherently dangerous due to pathogen transmission, and risky because of confrontations with predators. Recent ecological research paints a dramatically different picture. Carrion proves more dependable than previously believed and becomes particularly abundant during food shortages when other resources dwindle. When large terrestrial or marine mammals die, they provide tons of accessible food that multiple scavenger species can share simultaneously.

Humans possess remarkable adaptations for efficient scavenging. The acidic pH of human stomachs acts as a natural defense against pathogens and toxins present in decaying meat. Fire use for cooking further reduced infection risks considerably. Our ability to cover long distances with minimal energy expenditure gave early humans a distinct advantage in locating carrion across vast territories. These physiological traits combined with behavioral and technological innovations created a powerful scavenging toolkit.

Language development, even in its earliest forms, enabled collective organization for finding large animal carcasses and coordinating efforts to drive predators away from kills. Simple stone flakes could slice through thick hides to access meat, while hammer stones cracked bones to extract nutrient-rich fat and marrow. This technological capacity transformed scavenging from opportunistic feeding into systematic food procurement.

The 1960s discovery of meat consumption evidence at African archaeological sites triggered heated debates. Researchers fixated on determining whether early hominins hunted animals or scavenged carcasses left by predators. This inquiry reflected cultural biases that positioned hunting as advanced behavior and scavenging as primitive. Scientists constructed a linear evolutionary narrative where hominins quickly graduated from scavenging to hunting large prey once they developed appropriate technology.

That perspective mirrored broader attitudes toward carnivores, with large predators viewed as superior members of the food chain and scavengers relegated to subordinate, less admirable roles. Modern ecological studies have thoroughly debunked this hierarchy. All carnivorous species consume carrion to varying degrees, and contemporary hunter-gatherer societies continue practicing scavenging alongside hunting and plant gathering.

The research team emphasizes that scavenging required substantially less effort than hunting while providing comparable nutritional returns. This efficiency made it an indispensable complement to other subsistence strategies throughout human history. Rather than representing a developmental stage our ancestors outgrew, scavenging remained a vital survival tool that populations returned to repeatedly across evolutionary timescales.

The authors draw a provocative parallel to a famous phrase in paleoanthropology. If eating meat made us human, they argue, then eating carrion equally deserves credit for shaping our species. Scavenging was not marginal behavior but a cornerstone of human adaptation that continues influencing modern populations.