Archaeologists excavating in southern France have uncovered more than 160 cremation burials that illuminate Roman funerary practices between the first and third centuries A.D. The graves, discovered at the ancient city of Olbia on the French Riviera, reveal detailed cremation processes and unique methods for honoring the dead through liquid offerings.

Olbia began as a fortified Greek settlement around 350 B.C. in what is now southern France. The geographer Strabo identified it as a city of the Massiliotes, people from nearby Massilia—modern-day Marseille. When Julius Caesar captured Marseille in 49 B.C., Olbia transitioned into a Roman city focused on trade and thermal baths. The French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (Inrap) conducted the excavations that exposed the extensive burial ground.

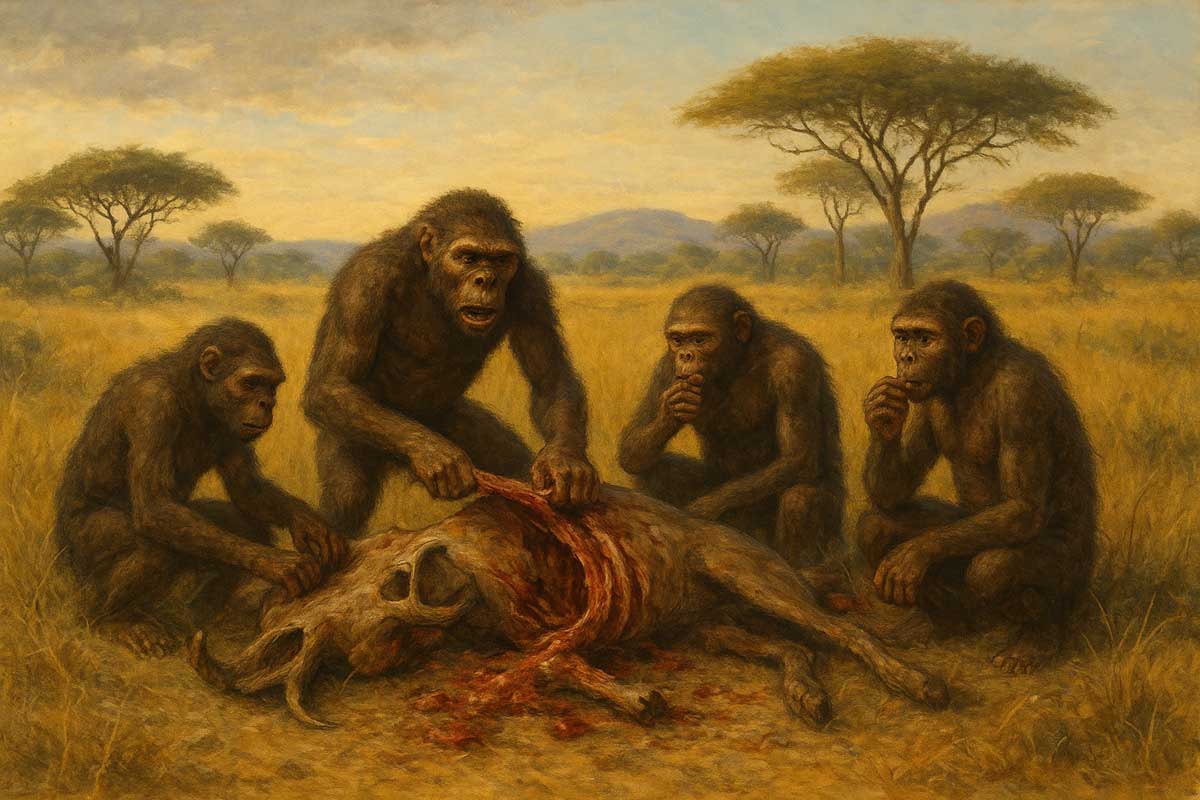

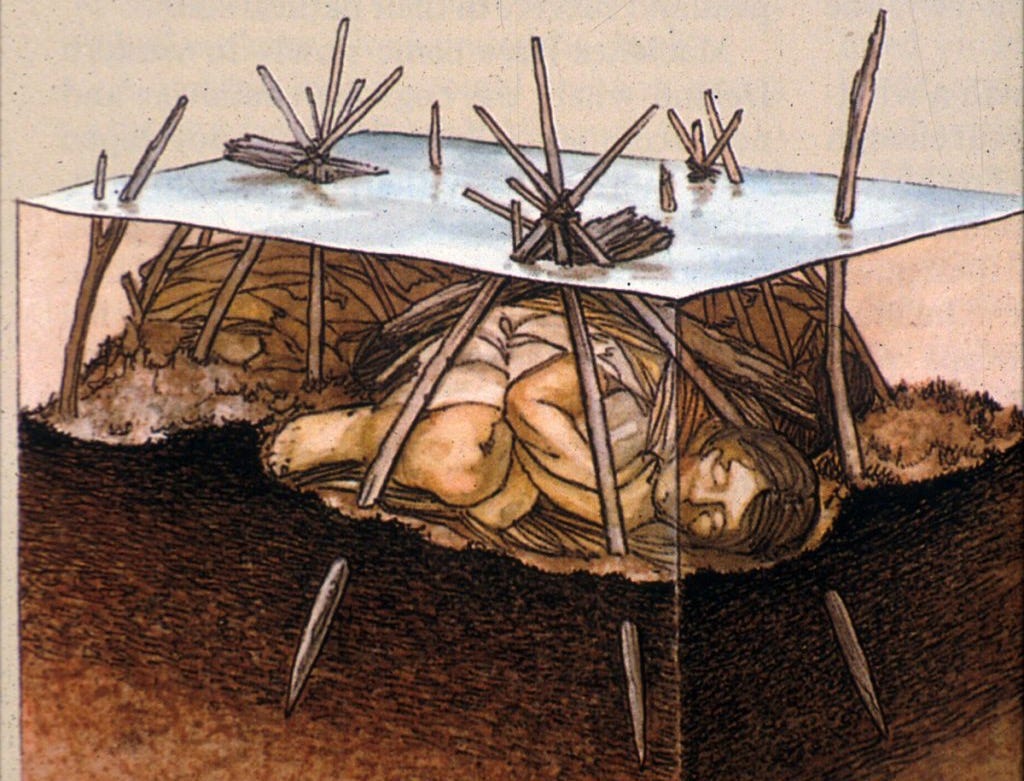

The cremation graves demonstrate step-by-step funerary procedures. For most burials, relatives placed bodies on wooden stands constructed over square pits. As pyres burned, intense heat caused the stands to collapse, dropping remains into the pits below. Bones whitened, twisted and cracked from the flames. Glass objects melted completely, bronze artifacts warped from the temperature, and soot covered ceramic vessels placed with the deceased.

After cremation, families handled remains differently. Some pits were covered with roof tiles and filled with dirt, transforming the cremation site directly into a burial location. Other pits were partially or completely emptied, with bones collected and placed in small piles or perishable containers before burial. This departure from typical Roman custom, which involved collecting bones in glass, ceramic or stone urns, suggests social or cultural differences within Olbia’s population.

A distinctive feature sets Olbia’s burials apart. Most graves incorporated libation channels constructed from repurposed amphora pieces that extended above ground even after burial. These tubes allowed families to pour liquids—wine, beer, or mead—directly into graves to honor deceased relatives or ensure their protection in the afterlife. The channels enabled continued interaction with the dead during Roman feast days dedicated to honoring ancestors.

Families could visit on specific dates throughout the year, symbolically feeding their loved ones through these permanent conduits. The Feralia on February 21 and the Lemuralia on May 9, 11 and 13 were Roman festivals when the living commemorated the dead through ritual offerings. The amphora tubes maintained a physical connection between the living and deceased, transforming graves into accessible sites for ongoing veneration rather than sealed memorials.

The varied burial practices at Olbia reflect the complexity of Roman funerary customs during the imperial period. The careful archaeological work documented how individual families approached death differently while operating within broader Roman cultural frameworks. Some followed standard procedures closely, while others adapted traditions to local preferences or personal circumstances.

“These discoveries remind us that ancient funerary rites were rich, varied, and imbued with multiple meanings, some of which remain mysterious even today,” Inrap representatives stated. The physical evidence of cremation—melted glass, warped bronze, soot-stained ceramics—provides tangible proof of the intense rituals families performed to transition their dead from the living world to the afterlife.

Featrured image: Two libation tubes that were found at Olbia in France. (Image credit: Tassadit Abdelli / Inrap)