A decades-old archaeological puzzle in Peru’s Pisco Valley may finally have an answer. More than 5,200 circular depressions carved into the hillsides of Monte Sierpe have baffled scientists since aerial photographs revealed their existence in 1933. Advanced drone mapping and soil analysis now point to a surprising dual purpose: an ancient trading hub that imperial authorities later converted into a sophisticated record-keeping installation.

The holes span 1.5 kilometers across southern Peru’s desert terrain, each depression measuring 1 to 2 meters in diameter and up to 1 meter deep. Their arrangement in precise rows and segmented blocks suggested intentional design, yet theories about their function ranged wildly—from water collection and fog capture to defense systems and gardens. Dr. Jacob Bongers from the University of Sydney led research that has produced the first concrete evidence about how ancient populations actually used this massive landscape modification.

Dr. Jacob Bongers, a digital archaeologist at the University of Sydney and lead author of the study published November 10 in the journal Antiquity, employed advanced drone technology to map the site. His team discovered numerical patterns in the layout suggesting deliberate design rather than random placement. “Why would ancient peoples make over 5,000 holes in the foothills of southern Peru? Were they gardens? Did they capture water? Did they have an agricultural function? We don’t know why they are here, but we have produced some promising new data that yield important clues and support novel theories about the site’s use,” Bongers said.

The most striking discovery emerged when researchers noticed the layout mirrored the structure of an Inca khipu found in the same valley. These knotted-string devices served as record-keeping tools for tracking information throughout the Inca Empire. “This is an extraordinary discovery that expands understandings about the origins and diversity of Indigenous accounting practices within and beyond the Andes,” Bongers explained. Researchers have previously found khipus alongside similar grids in Inca storage spaces, suggesting both locations were used to count and sort different goods.

Soil samples from the holes revealed traces of maize, one of the Andes’ most essential crops, along with reeds traditionally used for weaving baskets. Since maize pollen does not naturally travel far from the plant, researchers concluded humans deliberately brought it to Monte Sierpe. The presence of bulrush pollen, which the Chincha Kingdom used for basket-making, provided additional evidence. “These data support the hypothesis that during pre-Hispanic times, local groups periodically lined the holes with plant materials and deposited goods inside them, using woven baskets and/or bundles for transport,” Bongers said.

Monte Sierpe’s location strengthens the marketplace interpretation. The site sits between two Inca administrative centers and near a crossroads of pre-Hispanic roads. It occupies a transitional ecological zone called chaupiyunga between the Andes highlands and the lower coastal plain—an ideal meeting ground for trade between regions.

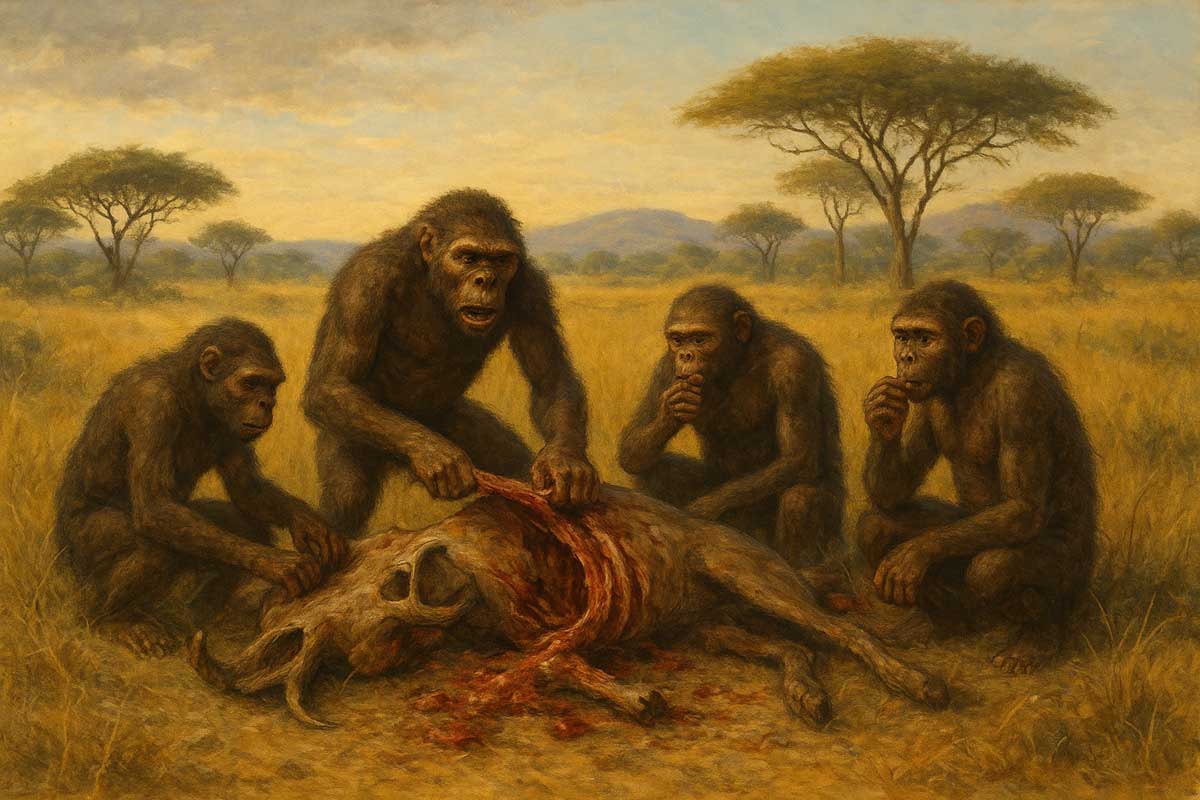

The powerful Chincha Kingdom, with a population exceeding 100,000 people, likely constructed the site between A.D. 1000 and 1400. “Perhaps this was a pre-Inca marketplace, like a flea market. We know the pre-Hispanic population here was around 100,000 people. Perhaps mobile traders (seafaring merchants and llama caravans), specialists (farmers and fisherfolk), and others were coming together at the site to exchange local goods such as corn and cotton,” Bongers suggested. Barter markets were common throughout the Peruvian Andes during this period, particularly along trade routes.

When the Inca Empire conquered the Chincha Kingdom in the 15th century, evidence suggests they repurposed Monte Sierpe for tribute collection and taxation. Slight variations in hole numbers across different blocks might reflect different tribute levels from nearby towns. “Fundamentally, I view these holes as a type of social technology that brought people together, and later became a large-scale accounting system under the Inca Empire,” Bongers said.

Professor Charles Stanish from the University of South Florida, senior co-author of the study, noted that despite its fame, Monte Sierpe received little professional archaeological attention since its 1930s discovery and limited 1970s surveys. “The site is isolated and not threatened by development. As a result, there has not been a sense of urgency,” he explained. Drone technology changed that equation by revealing mathematical patterning invisible from ground level or nearby hills due to persistent coastal haze.

“Until drone technology, the site of Monte Sierpe/Band of Holes was extremely difficult to map on the surface. One simply cannot get an accurate impression of the structured nature of the hole segments, even from the top of the mountain behind due to the permanent haze in the area,” Stanish said. “Once we had precision, low-altitude images it was immediately clear that this site was profoundly important and had to be scientifically studied.”

Professor Kirsten McKenzie, Director of the Vere Gordon Childe Centre at the University of Sydney, emphasized the research’s significance for combating misinformation. “Monte Sierpe is a high-profile site that attracts a lot of popular commentary online, including misinformation that threatens to overshadow Indigenous knowledge bases and community ownership over history and heritage,” she said. Stanish added that the site has long featured prominently in pseudoarchaeology discussions with rampant speculation. “One of the benefits of scientific work is the debunking of unsubstantiated claims that in many ways deprive Indigenous peoples’ rightful ownership of their past.”

Questions remain about why this monument appears only at Monte Sierpe rather than throughout the Andes, and whether it truly functioned as a “landscape khipu.” Stanish announced plans for additional work to determine the range and origins of various plants found at the site, particularly medicinal species. “With every identification of a new plant type, the Band of Holes becomes more intriguing,” he said.

Featured image: These holes at Monte Sierpe in Peru may once have held crops, goods and tribute, a new study suggests. (Image credit: C. Stanish; Antiquity Publications Ltd; CC BY 4.0)