Metalworkers on Elephantine Island near Aswan were deliberately producing arsenical bronze nearly 4,000 years ago using sophisticated alloying techniques, according to new research published in Archaeometry. The discovery overturns long-held assumptions about ancient Egyptian metallurgy and reveals technological innovation far ahead of what scholars previously credited to Middle Kingdom craftsmen.

The study, led by Ing. Jiří Kmošek of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and the Czech Academy of Sciences, along with Dr. Martin Odler of Newcastle University, identified the first direct evidence of controlled arsenical bronze production in Egypt. Dating to approximately 2000 to 1650 BCE during the Middle Kingdom period, the findings center on a metallurgical by-product called speiss that ancient metalworkers used intentionally as a reagent.

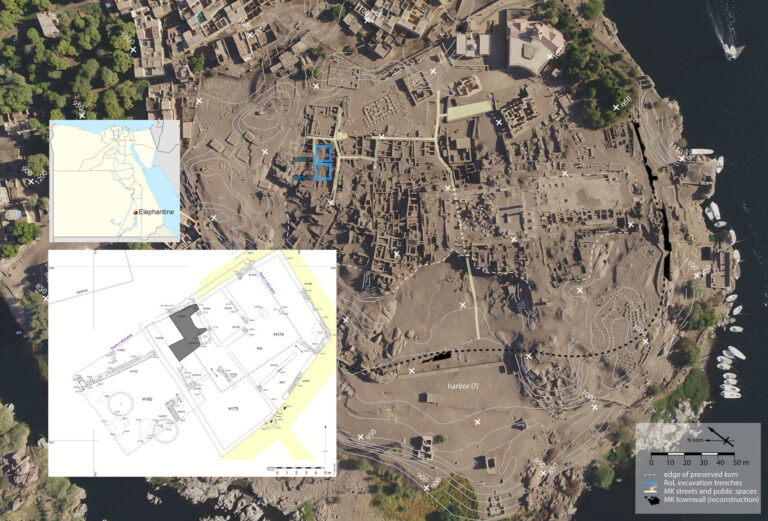

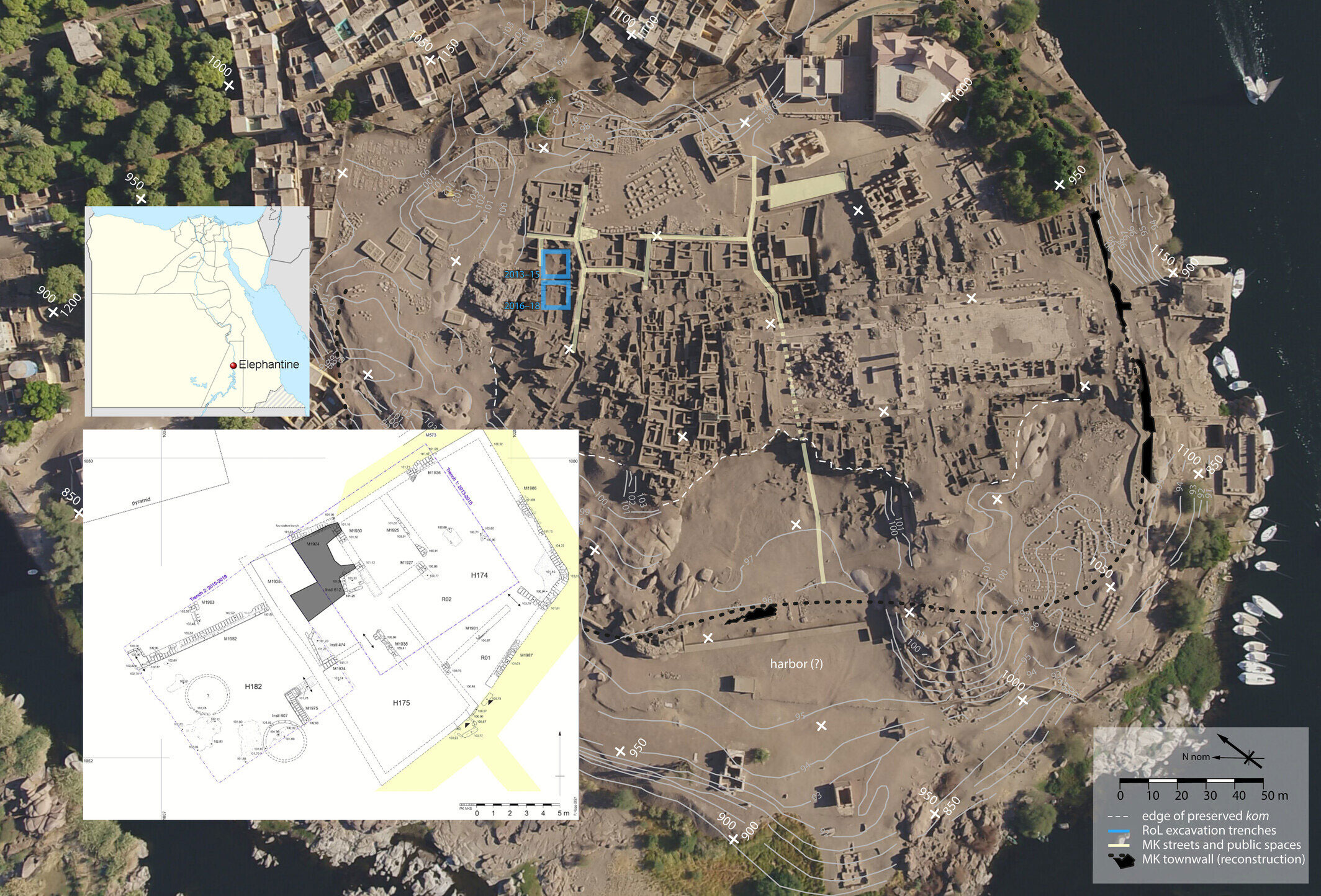

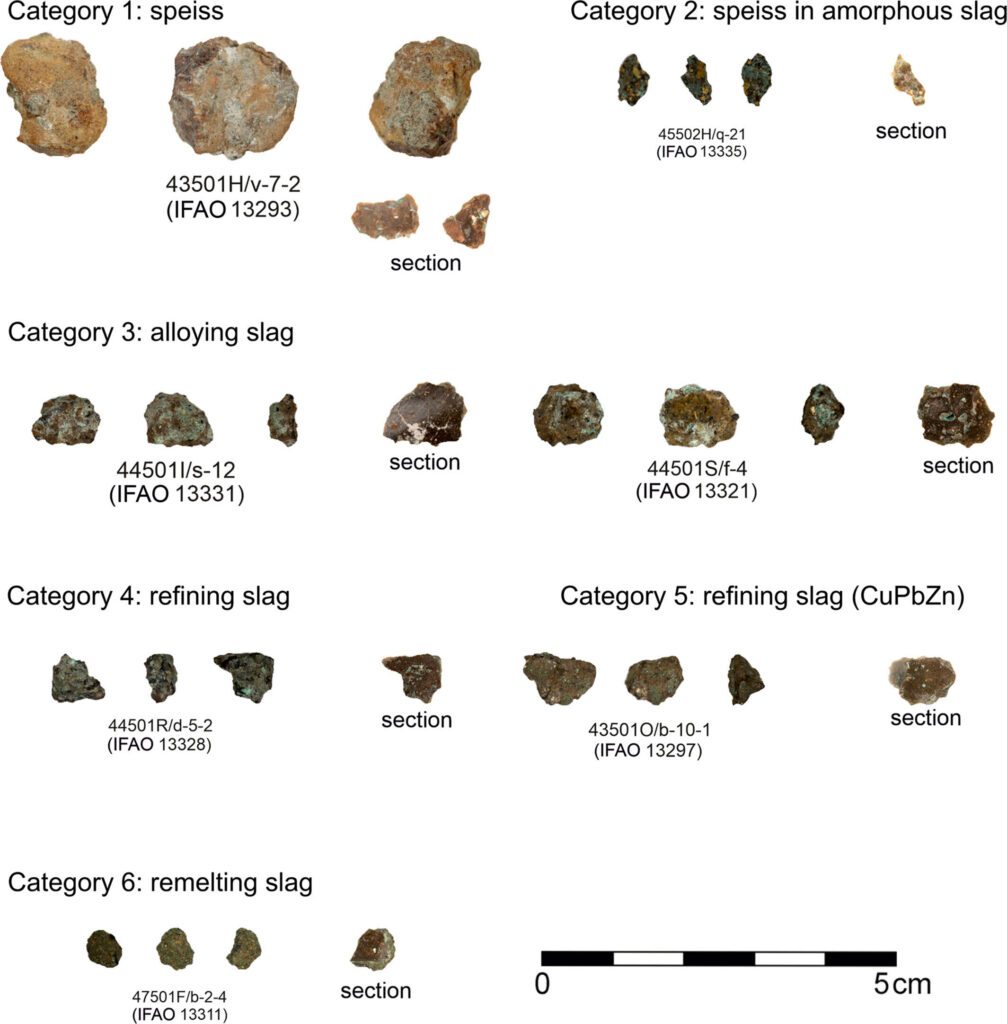

Speiss is a slag-like alloy containing high concentrations of arsenic, iron, and in this case several percent lead. Researchers found fragments of this material in House 175 within the Elephantine settlement area, providing concrete proof that Egyptian metallurgists deliberately manipulated metal composition rather than relying on naturally contaminated ores.

For decades, scholars assumed arsenical copper in ancient Egypt resulted from accidental inclusion of trace arsenic in copper ore deposits. The new evidence tells a different story. Middle Kingdom metalworkers added speiss to molten copper in ceramic crucibles through a controlled cementation process, enhancing the hardness and durability of bronze. These improved qualities were essential for manufacturing tools, weapons, and ritual objects that required superior strength.

“This find radically alters our perception of Egyptian metallurgy, demonstrating that technological innovation was already well established by the early second millennium BCE, and before, as we have identified even earlier fragments of speiss, which will be investigated later on,” said Dr. Odler, corresponding author of the study.

The research team worked with metallurgical remains excavated from Elephantine Island, a concession of the German Archaeological Institute’s Cairo Department. They employed laboratory facilities at the Institut français d’archéologie orientale and the Desert Research Center in Cairo, with approval from Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. The work took place within the framework of the “Realities of Life” subproject led by Dr. Johanna Sigl.

Advanced analytical techniques revealed the ancient production process in detail. Using portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF), optical microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX), researchers examined metallurgical debris dating to Egypt’s 12th Dynasty in the 19th century BCE. The compositional and microstructural analyses showed that speiss introduced not only arsenic but also trace amounts of antimony and lead into the final metal.

“The integration of speiss indicates a much deeper understanding of alloy production processes than previously credited to ancient Egyptian craftsmen and provides fresh insights on their capabilities,” Kmošek noted.

These additional elements affected both the physical properties of the finished bronze and the isotopic composition that modern researchers use to trace metal origins. The presence of lead from speiss complicates provenance studies by shifting the lead isotope ratios of copper ores, making it harder to determine where raw materials originally came from.

The source of the speiss itself remains uncertain, though researchers believe it was most likely processed from arsenopyrite ores found in Egypt’s Eastern Desert. This suggests Egyptian metallurgists either procured these specialized materials themselves or obtained them through local non-Egyptian populations living in desert regions. Either scenario points to sophisticated resource procurement systems and possible trade networks operating during the Middle Kingdom.

The discovery reveals a society capable of refining complex metallurgical techniques nearly four millennia ago, well before such methods became widespread in other regions. The controlled use of speiss demonstrates not only advanced scientific knowledge but also sophisticated understanding of material transformation and resource management.

This technological achievement places Middle Kingdom Egypt among the most advanced metallurgical cultures of the early second millennium BCE. The deliberate manipulation of metal composition through chemical additives shows systematic experimentation and knowledge transfer between craftsmen. Such expertise would have required generations of accumulated experience and careful observation of how different materials affected final products.

The findings have broader implications for understanding ancient trade networks and technological exchange. Speiss production typically requires access to specific mineral deposits and knowledge of extraction processes. Its presence on Elephantine Island indicates either direct mining operations in the Eastern Desert or established trade relationships with communities that specialized in processing arsenopyrite ores.

Elephantine Island occupied a strategic position near Egypt’s southern border, serving as a major trade hub connecting the Nile Valley with Nubia and regions beyond. The sophisticated metallurgy practiced there suggests the settlement functioned not only as a commercial center but also as a location where specialized craftsmen worked with imported materials and advanced techniques.

The discovery opens new questions about how metallurgical knowledge spread across ancient Egypt and the Near East. Did Egyptian craftsmen develop these techniques independently, or did they adapt methods from other cultures? How widely were these production methods practiced beyond Elephantine Island? The identification of earlier speiss fragments mentioned by Dr. Odler suggests this technology may have even deeper roots than currently documented.

Future research will likely focus on identifying additional production sites and tracing the origins of materials used in arsenical bronze manufacturing. Understanding the full extent of this technological tradition could reshape narratives about innovation and knowledge transfer in the ancient world.

The study demonstrates that ancient Egyptian metallurgy involved far more deliberate experimentation and technical sophistication than previously recognized. Rather than passively accepting whatever metals nature provided, Middle Kingdom craftsmen actively transformed raw materials to achieve specific desired properties, showing scientific reasoning that rivals modern metallurgical principles.

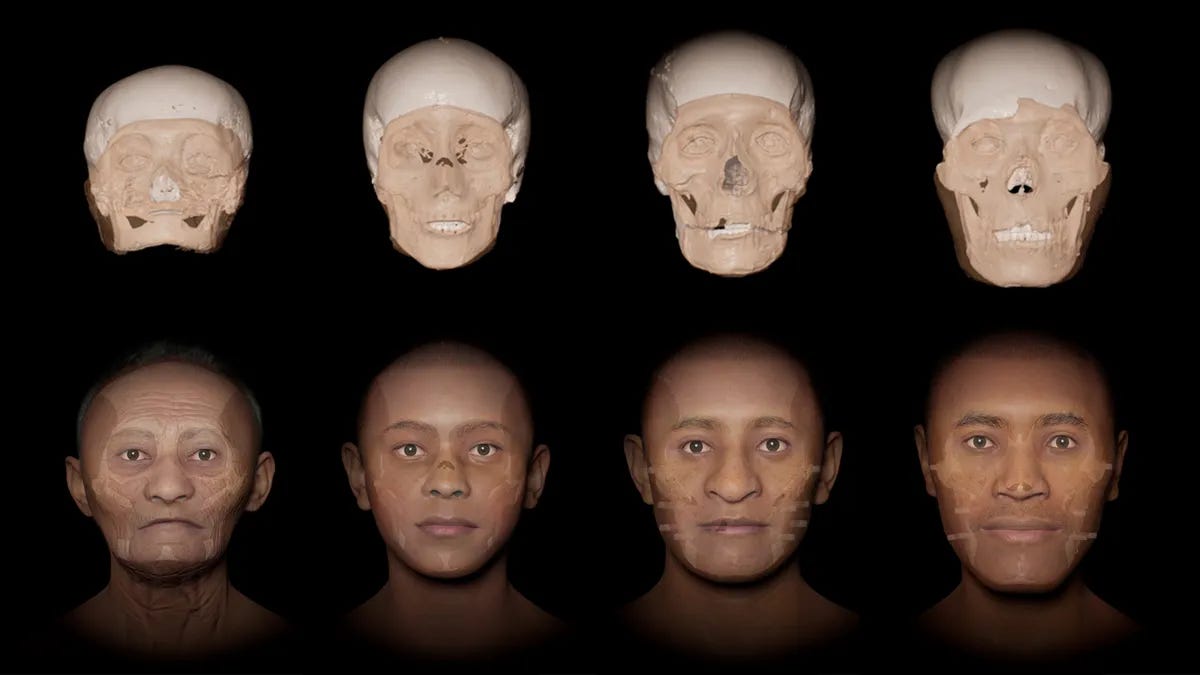

Featured image: The background shows an aerial orthophotograph of the southern part of Elephantine Island with the Realities of life excavation squares highlighted in blue, south-east of the Dynasty 3 granite pyramid. Credit: Archaeometry (2025). DOI: 10.1111/arcm.70008