A 3,000-year-old Maya complex in southeastern Mexico functioned as a city-sized map of the cosmos, new research reveals. Aguada Fénix, the oldest and largest monumental architecture in the Maya region, was designed as a cosmogram representing how its builders conceived universal order and the passage of time.

The artificial plateau with connecting causeways, canals and corridors spans 9 by 7.5 kilometers—comparable to or larger than later Mesoamerican cities like Tikal and Teotihuacán. Built around 1050 B.C. and occupied for roughly 300 years before abandonment around 700 B.C., the site predates the Maya writing system, leaving no textual records of its purpose. Takeshi Inomata, Regents Professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona, led the study published Wednesday in Science Advances.

The site remained hidden beneath forest and agricultural fields until remote sensing equipment spotted it from an airplane. LiDAR technology, which revolutionized archaeology by revealing structures obscured by vegetation, first made Aguada Fénix public in 2020. The main platform once stood nearly 15 meters high, but without stone construction, it easily disguises itself as a natural hill. Most of the plateau now serves agricultural purposes, making the monumental earthworks nearly invisible from ground level.

Between 2020 and 2024, Inomata’s team excavated key locations, studied soil cores and conducted additional LiDAR surveys. They discovered a design based on increasingly larger crosses with a cruciform pit containing precious ritual artifacts at the center. A large rectangular plaza, capable of accommodating over 1,000 people, sits at the intersection of two long thoroughfares running north-south and east-west, possibly used as processional routes.

At the plaza’s center, archaeologists unearthed a cruciform pit with stepped access from the platform above. Within it lay a smaller pit containing jade artifacts arranged in a cross formation. Pigments tied to specific cardinal directions accompanied these offerings: blue for north, green for east, yellow for south, and a red shell possibly representing west. “It’s like a model of the cosmos or universe,” Inomata explained. “They thought that basically the universe is ordered based on this cruciform pattern, and then that’s tied to the order of time.”

The monumental structure’s east-west axis aligns with sunrise on October 17 and February 24. The 130-day interval between these dates equals half of 260 days—the main ritual calendar used throughout Mesoamerica. This astronomical precision suggests the site served as a ceremonial gathering place during significant calendar dates, likely in the dry season when people could more easily congregate.

Excavations revealed greenstone ornaments possibly depicting a crocodile, a bird and a female giving birth, alongside ceramic vessels that held ceremonial significance. The canals, which aggregate 193,000 cubic meters in volume, appear to have served no practical purpose. A small lake provided water, but its size would have prevented the canals from staying filled for extended periods. No evidence of agricultural irrigation emerged, ruling out crop cultivation as the canals’ function.

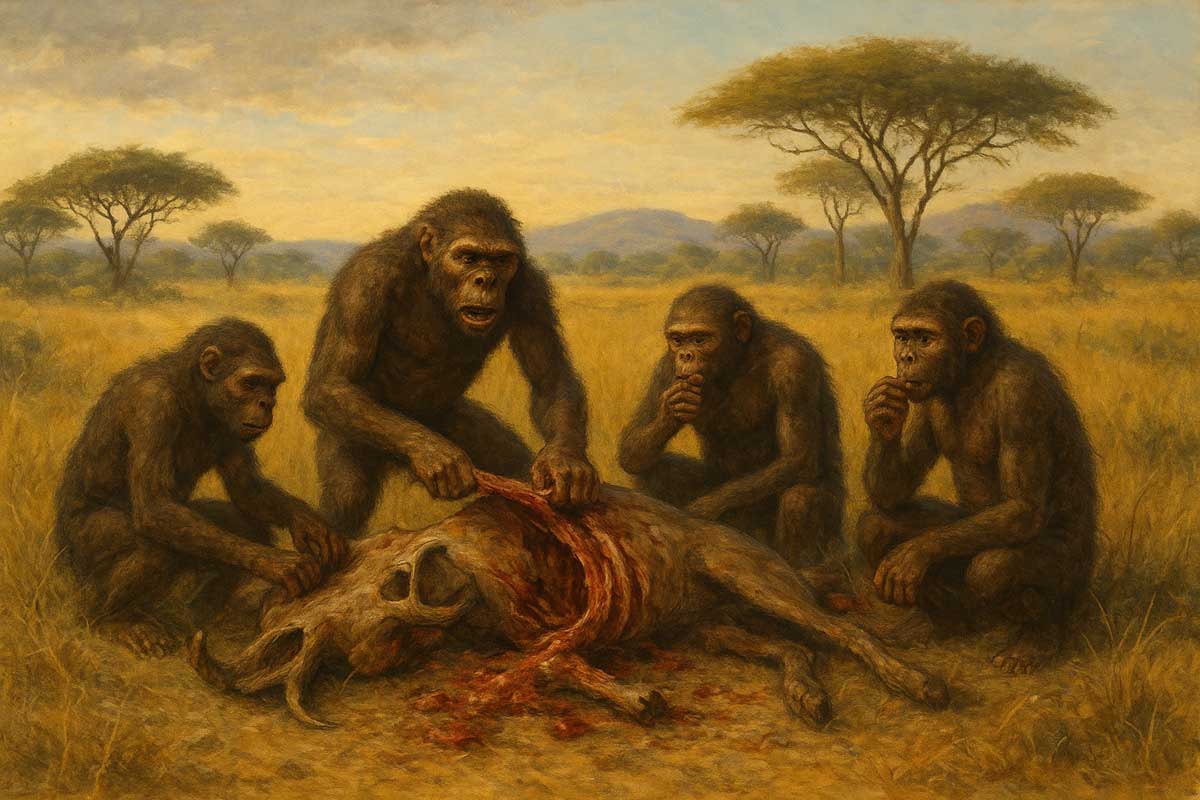

The site represents a pivotal moment in Maya development. “Before this site there’s no substantial construction. There’s really nothing archaeologically; they were not even using ceramics,” Inomata noted. Construction required more than 1,000 people spending several months yearly over multiple years. The canals would have demanded 255,000 days of labor by a single person, while the 3.6 million cubic meter main plateau would have required 10.8 million labor days. The canals remained unfinished when the site was abandoned.

Crucially, the team found no evidence of social hierarchy—no statues of rulers, no palaces for elites, and no signs of coerced labor. The dwellings suggest the site wasn’t permanently occupied by large populations. Verónica Vazquez Lopez, a lecturer in Mesoamerican archaeology at University College London and study coauthor, emphasized how the communal nature of construction distinguished Aguada Fénix from later Maya cities and Egyptian pyramids built through compulsory labor.

“We have this perception that to do a big thing, you have to have hierarchical organization and that’s the way it happened in the past,” Inomata said. “But now we are getting an image of the past which is different. People also did big things by organizing themselves, getting together and working together.” Large construction events likely involved feasting, goods exchange between groups, and opportunities to meet potential mates, providing additional incentives for gathering.

Stephen Houston, a Brown University professor of anthropology, called the research thrilling. “The finding here is that a common theme in Mesoamerican societies—situating the world according to ritual directions and colors attached to them—are laid out explicitly, and at an early date, at Aguada Fénix,” he said. “This research is part of a larger intellectual movement in archaeology, to show that large constructions can take place in situations of relative equality.”

Andrew Scherer, also a Brown University professor, noted the site’s importance for understanding a poorly documented period. “There was a tremendous amount of labor invested at Aguada Fenix—in not only raising its earthworks but also in importing and carving a large number of greenstone objects—and in no instance is there a clear case of something built or manufactured to celebrate a ruler or a particular subset of individuals,” he said. Leading figures with specialized knowledge of astronomical observations and calendrical calculations likely designed the cosmogram, but construction appears to have been a celebrated communal activity rather than imposed obligation.

Feature image: Archaeologists found a cross-shaped area at the Aguada Fénix site in Mexico. (Image credit: Takeshi Inomata)