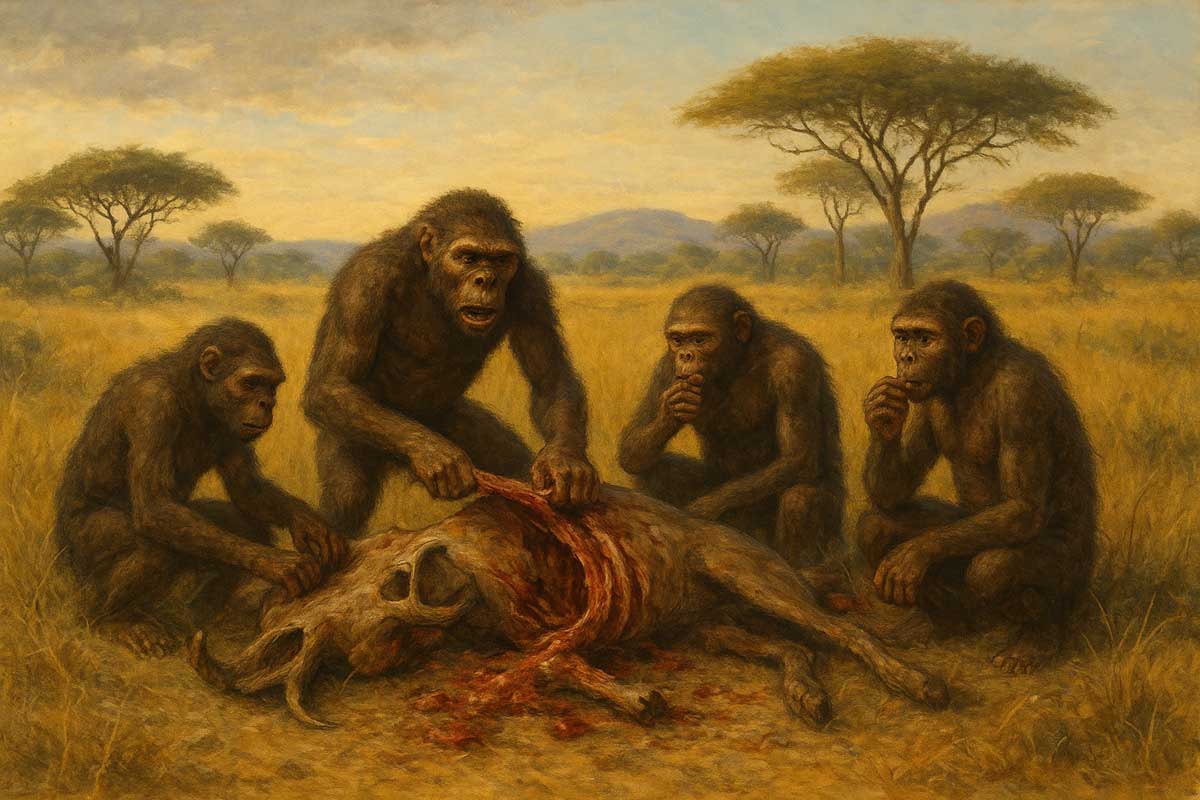

Scientists have long believed that early humans conquered the food chain approximately 2 million years ago in East Africa. New evidence suggests this evolutionary milestone may have occurred much later than previously thought.

Fresh analysis of fossilized remains challenges the established narrative about Homo habilis, revealing that these ancient hominins likely fell victim to leopard attacks rather than dominating as apex predators. The discovery fundamentally reshapes our understanding of when humans first gained the upper hand against dangerous carnivores.

Homo habilis earned recognition as potentially the first true human species among anthropologists. These hominins crafted the earliest known stone implements, called the Oldowan Toolkit, within Tanzania’s famous Olduvai Gorge. Archaeological evidence from the same location indicates prehistoric humans began processing animal carcasses left behind by large predators like big cats.

This butchery evidence previously supported theories that H. habilis possessed sufficient defensive capabilities to ward off carnivores while simultaneously stealing their kills. Earlier hominin species including Paranthropus and various Australopithecines definitely served as prey for leopards, lions, and similar large felids throughout this period.

Researchers conducted detailed reexamination of two H. habilis specimens recovered from Olduvai Gorge. Both fossils display clear evidence of animal bite damage, including the 1.85-million-year-old holotype specimen that serves as the defining example for the entire species’ physical characteristics.

Earlier interpretations attributed these markings to hyena scavenging behavior on already deceased hominin bodies. Advanced artificial intelligence analysis now contradicts this explanation. The technology identified leopard tooth patterns with greater than 90 percent accuracy, indicating active predation rather than post-mortem scavenging.

Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo, the study’s lead author, describes how scientific perceptions have shifted dramatically. Previous research depicted H. habilis as “the first conqueror of the trophic pyramid” and successful “scavenger-hunter” capable of defending against carnivorous threats.

The new findings paint a starkly different picture. Both analyzed specimens suffered leopard predation identical to patterns observed in earlier Australopithecine remains. These results effectively challenge H. habilis‘s elevated status within early human evolution.

If both individuals represent typical examples from the broader H. habilis population at Olduvai, their shared predation experience reveals this species’ fundamental inability to handle threats from medium-sized carnivores like leopards. The implications extend far beyond individual cases.

“The implications of this are major, since it shows that H. habilis was still more of a prey than a predator,” the research team concluded. This revelation essentially demotes the species from its previously assumed position as humanity’s first apex predator.

The study raises critical questions about which human ancestor actually achieved dominance over dangerous carnivores. Homo erectus emerges as the most likely candidate for this evolutionary breakthrough. This species coexisted with H. habilis but demonstrated superior terrestrial adaptations compared to their more arboreal relatives.

H. erectus populations spent significantly more time on open ground rather than seeking safety in trees. Their enhanced terrestrial lifestyle may have provided better opportunities to develop effective anti-predator strategies and successful competition for carnivore kills.

Domínguez-Rodrigo emphasizes the dramatic reassessment required by these findings. Rather than representing humanity’s first step toward food chain dominance, H. habilis appears to have remained vulnerable to the same predatory pressures that threatened earlier hominin species.

The research appears in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, contributing crucial data to ongoing debates about early human survival strategies. These results suggest the transition from prey to predator occurred later in human evolution than previously assumed.

Featured image: Leopard tooth marks were found on this Homo habilis jawbone. Image credit: Vegara-Riquelme et al., Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (2025)